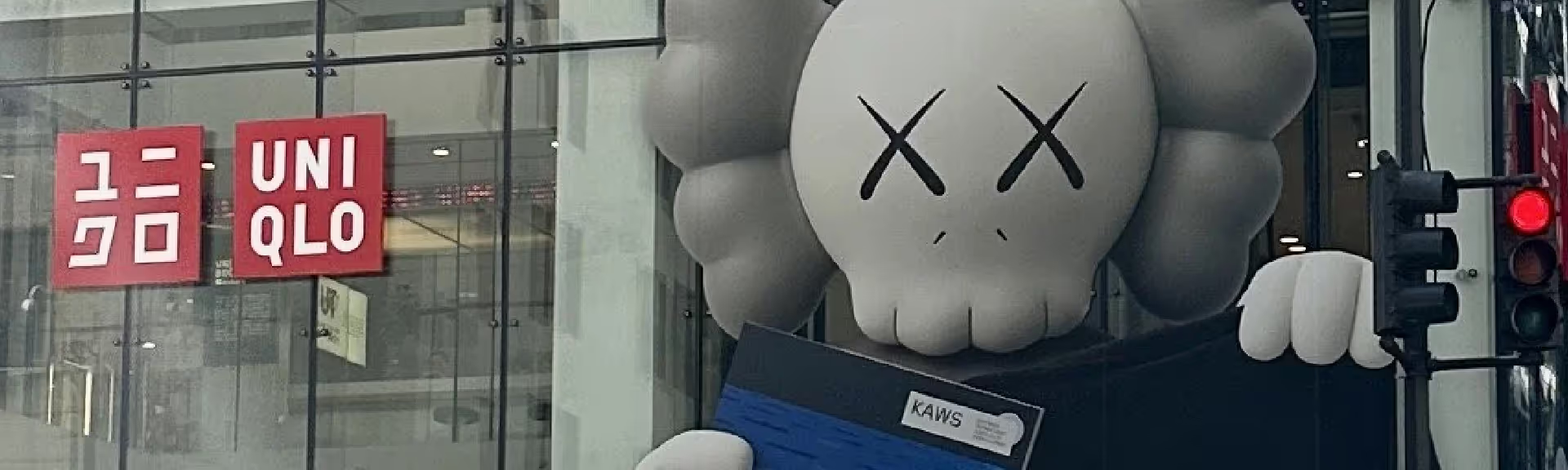

The latest in its ongoing series of artist collaborations, UNIQLO announced that KAWS — known for his cartoonish, hollow-eyed figures called “Companions” that blur the line between collectibles and contemporary art — will be the fashion brand’s first artist in residence.

As artist in residence, KAWS will support the UNIQLO’s aim to democratize art and design for a global audience through events staged at stores worldwide and collaborations with museum partners. He will also participate in creating new LifeWear collections, the first of which will be released in the fall/winter 2025 season.

Historically, artist collaborations have largely been seen through the lens of hype: capsule collections, sneaker drops, pop-up installations.

By definition, a brand is easy to define. It’s got a border, a frame, a centre, a product, a mission. An artist, however, and art itself, in the myriad forms it takes, is a much more amorphous state of being, one without a clear definition or clear boundaries, often without a frame.

And an artist’s mission may be a million miles from any path a brand treads, and the process of its becoming even further away from the world of briefs, vested interests and relentless revisions and amends that any engagement with brand communications entails. Just watch BBDO’s uncomfortably hilarious Museum Worthy spot for the AICP Awards.

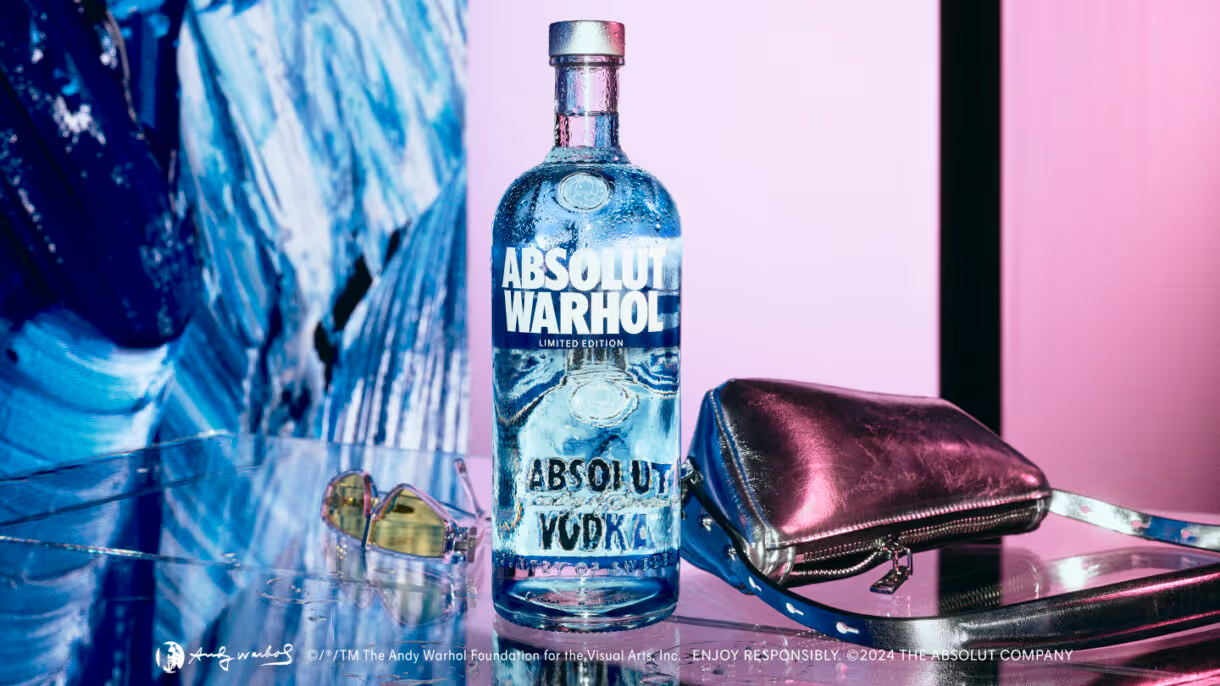

Cast back to the last century, however, and there are some surprising couplings — between Salvador Dali and Chupa Chups, or the more celebrated Absolut Vodka campaign, which started its ‘Absolut Collaborations’ in 1985 with former advertising industry illustrator, Andy Warhol, and has built up a portfolio of vodka label art that is past the 800 mark.

Warhol’s first piece is, in fact, reissued last year in a special limited edition, while the likes of Ed Ruscha, Damien Hirst, Chris Ofili and Louise Bourgeois and her spiders have all engaged to create work for the vodka brand.

Takashi Murakami, a renowned Japanese artist, has a proven track record of collaborating with luxury fashion brands. Back in 2002, he teamed up with Louis Vuitton to create a collection that incorporated his vivid floral and skull patterns. The partnership was immensely prosperous and played a crucial role in solidifying Murakami's position as one of the most desirable contemporary artists.

In 2022, anonymous street artist Banksy unwillingly — and unknowingly, collaborated with fashion brand Guess and Brandalised on a collection that featured his signature graffiti-style designs. The collection included t-shirts, hoodies, and other streetwear-inspired pieces that featured Banksy's images of rats, monkeys, and other animals. And Banksy was outraged.

As a result, he took to social media and encouraged shoplifters to head on over to the London Guess store, causing the shop to shut its doors temporarily and stock up on security outside its storefront. This caused a social storm, with many arguing over who has the rights to reuse public graffiti for profit.

Given the gulf between the two, it’s a wonder that brands and artists get together at all. But the narrative in 2025 is shifting. Now, as the KAWS–UNIQLO partnership suggests, collaborations are less about novelty and more about value alignment, storytelling, and audience engagement.

Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art. (Andy Warhol)

Collaborations between artists and brands have great potential, but how they create needs to be authentic and respectful.

Creating new work with artists is exciting for a brand, but authentic collaborations and understanding of process is so important. Tapping into why an artist makes their work in the first place and using its originality and purpose will connect with its power.

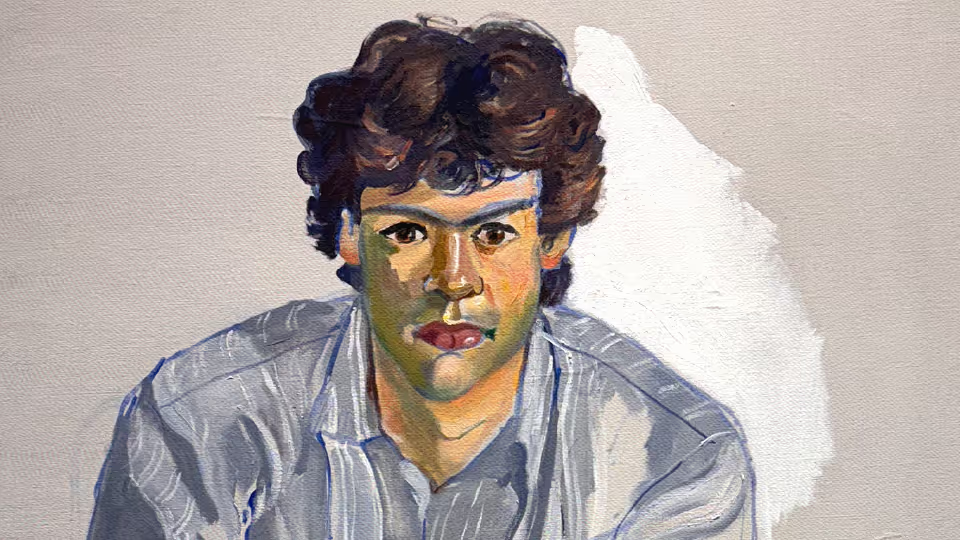

Painter Alex Merry and her work for Gucci is an example of a successful artist-brand collaboration. According to the artist, Gucci provided the space and inspiration for Merry to do what she’s known for, and what she does best’. It resulted in a “brilliant experience” according to Merry, with a unique outcome for Gucci.

Damien Bradfield, co-founder of WeTransfer, and an online gallerist for dozens of rising fine artists, describes Banksy as one of the masters of marketing, as canny as the canniest brand. Bradfield believes Banksy understands secrecy and scarcity better than anybody, and there’s still this mystique around him that people actually want to carry on – no one really wants to burst the bubble.

In recent years WeTransfer has hosted new contemporary art on its WePresent platform. Perhaps because it is a delivery system and not a product per se, without the weights and measures of ethics and politics that come packed with any product on a shelf, it’s become a popular brand platform for artists. WePresent gives money or media to support artists, and its ambition is to be a patron of the arts.

Artists love WePresent because it doesn't ask for brand collaboration, artists don’t need to endorse it and it gives them carte blanche.

One of the best was an installation with Marina Abramovic called Traces, an online experience that mirrored her MoMo experience.

The debate of ’selling out’ surely lies with the end creative result and why that partnership even happened, rather than working with a brand per se. The likes of the Keith Haring Foundation is a prime example of successfully licensing artwork to provide grants for children affected by HIV/AIDs.

It’s in the spirit of business meets art that Warhol would’ve been proud of. For at the end of the day, as he once said: “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.”